Final - Module 503

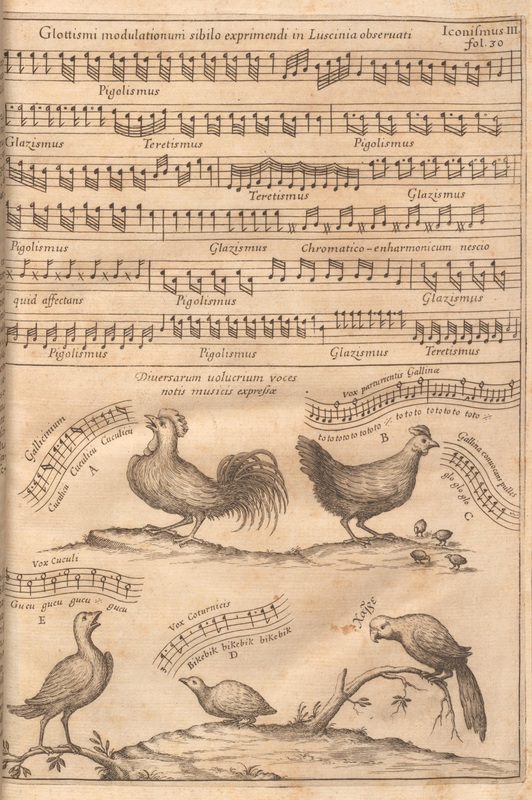

Musurgia Universalis: Bird Songs. Athanasius Kircher, Vol. I opp. 30, etching, Rome, 1650. Division of Rare Book and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, ARTstor. Web. April 6, 2016. The parrot, lower right, is saying "Hello" in Greek.

Musurgia Universalis: Bird Songs. Athanasius Kircher, Vol. I opp. 30, etching, Rome, 1650. Division of Rare Book and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, ARTstor. Web. April 6, 2016. The parrot, lower right, is saying "Hello" in Greek.

Between the Song and the Silence

Turning memory into narrative is common practice in the human experience. Our memories become entwined with the recollections of others, so that each time we recall them they subtly change. This layering of narrative, or collective memory, can serve to reinforce our perceptions of both our past and potential futures [1, 2].

I am in the process of creating a libretto for a place-specific performance. The calls of extinct or threatened birds will be performed within a narrative crafted from my memories of an encounter between two elderly birdwatchers.

In using these bird calls, I hope to be able to transport my audience to an interior emotional setting whereby they may feel more sensitive to the absences in their environments.

As Ghassan Hage has said, “Song and music in particular, with their sub-symbolic meaningful qualities are often most appropriate in facilitating the voyage to this imaginary space of feelings”[3]. So too can sounds transport us [4-6].

The research with which I am engaged had its genesis in reminiscences at our family cottage in the Laurentian mountains of Québec about things no longer seen nor heard.

We all reminisced about what it used to sound like up there, about the complexity of the combined sounds of birds and wildlife. How the bass cacophony of bullfrogs in the evening could keep you from falling asleep, while the howling of the wolves nearby would make you shiver deliciously under the covers. The banshee laughing and wailing of loons would fade away to be replaced by the dignified hooting of owls.

It doesn’t sound like that anymore. To hear one bullfrog is cause to “shush” everyone, while the rare occasion that the wolves sing at night is remarked upon by all the neighbours, and is something you’d tell the cashier about at the store in town.

Visitors often remark now about the quality of the silence there, about how “beautiful and quiet” it is.

Is It?

We are firmly entrenched in a soon-to-be christened epoch, dubbed the “Anthropocene” by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and diatom biologist Eugene Stoermer. It is defined as a new geologic age in which the activities of humans have significantly impacted our global climate, environment and ecology to such an extent as to permanently mark the lithosphere. This age is commonly referred to as the “sixth extinction”, marked by rapid declines in biodiversity as more and more species become vulnerable to changes in their ecologies [7].

Reflecting upon what narrative I wanted to create, I realized how truly little we are aware of these losses in our surrounding environments. As the voices of species are extinguished, are we aware of these absences? Looking around our urban environments, we are confronted with false abundance – we may see a profusion of birds, but a paucity of species [8]. Have our environments become so cluttered with the sonic detritus of contemporary urban life that we are oblivious? Perhaps we confuse what we now hear with memories of what we once heard, or confabulate?

The writer Eva Hoffman declared, “Loss leaves a long trail in its wake. Sometimes, if the loss is large enough, the trail seeps and winds like invisible psychic ink through individual lives, decades, and generations” [9]. It has been has argued that “sharing memory is our default”, and that complex emotions such as grief, love and regret depend upon our personal memories and an awareness of the passing of time. Our imperfect recall is responsible for the endurance of the past within our present relationships [10, 11].

I thought about what the Laurentian forests and lakes would have sounded like in my grandparents’ time, and about the different species that they heard that I will never hear.

How could you describe the call of a bird you’d never heard? If you’d never heard it, could you truly miss it?

What remains between the song and the silence?

An encounter between two elderly birdwatchers spurred my interest in creating a work which not only speaks to my life-long fascination with birds, but examines this fascination in others. Through the use of birdcalls of extinct and threatened species, I wondered if it would be possible to foster a sense of awareness regarding what species we have already lost or are in the process of losing.

So what propelled me forward? Following a discussion with an ornithologist at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, I decided to see if I could get in touch with elderly birdwatchers who would have likely heard these species in the wild. Visiting a centenarian birdwatcher at a retirement home to look at his birdwatching diaries, and with the hope that I might be able to persuade him to do a few birdcalls, I was witness to a fascinating exchange. As he performed some bird calls for me, another elderly gentleman appeared in the doorway, and responded to the bird calls with calls of his own. The two engaged in a call and response of birdcalls for approximately thirty minutes. After the gentleman had left, I found out that due to dementia, he had been unable to hold conversations with others. Yet what I had witnessed was just that, using the voices of birds. It had been profoundly moving to watch and listen to the two men “converse”, and provoked a deeply visceral response in me.

What is it that makes birdsong so compelling? It would seem that it’s all in the genes. Charles Darwin believed that language acquisition is instinctual [12], and subsequent research by Noam Chomsky and his colleagues would seem to support this idea [13, 14]. Research has shown that the same set of genes that enables humans to speak also confers on birds the ability to sing [15-17]. It was further discovered that the way birds acquire specific birdsong seems to mirror the way humans acquire speech [17-20]. Dr. Doolittle’s exhortations to “talk to the animals” just might have some basis in fact.

Perhaps it also speaks to the notion of déjà vu, which refers to the phenomenon of feeling as though something is very familiar when in fact you are experiencing it for the first time. For Steve Goodman and Luciana Parisi,” déjà vu suggests time collapsed onto itself, perhaps some kind of mnemonic haunting or future feedback effect.” [21]. Paramnesia is usually described as a psychopathology in which events are remembered while being experienced for the first time. It is generally thought that this occurrence is far more commonplace than would be expected of a memory disorder. Henri Bergson described paramnesia as a “symptom that explains that there is a recollection of the present, contemporaneous with the present itself”[22, 23]. Thus the calls of songbirds may literally “speak” to our memories of nascent attempts to communicate conferring an uncanny familiarity with their songs.

It has been stated that “the importance of physical engagement with the world, through the senses, enables emotional expression to be made in artworks that can be perceived by both artist and audience”[24]. Furthermore, these memories of physical experiences spark creative cognition and stimulate the imagination. Mary Carruthers states:

“In Greek legend, memory, or Mnemosyne, is the mother of the Muses. That story places memory at the beginning, as the matrix of invention for all human arts, of all human making, including the making of ideas; it memorably encapsulates an assumption that memory and invention – what we now call creativity – if not exactly the same, are the closest thing to it. In order to create, in order to think at all, human beings require some mental tool or machine, and that machine lives in the intricate networks of their own memories. The requirement of memory for making new thoughts is at the heart of this traditional story [25].

Julianne Lutz Warren, a writer and conservation biologist, created a work entitled “Hopes Echo” for the Deutsches Museum in Munich (on exhibition until September 30, 2016). Her work concerns the “sound fossil” left by the huia bird of New Zealand, which became extinct in the beginning of the 20th century due primarily to habitat loss coupled with overhunting. There are no extant audio recordings of this bird – it became extinct before the technology was available to make field recordings. The Maori people regarded the huia as sacred, and those who were high status were accorded the honor of wearing its feathers or skins. To lure the birds when hunting, they learned to imitate its song. This was passed down through the generations, a practice that continued for decades after the bird became extinct. In 1954 a man named RAL Bateley made a recording of a Maori man, Henare Hkamma, whistling the huia’s call. Warren presents the audio recording of Hkamma’s bird calls with text drawing our attention to the fact that we have the calls of an extinct bird performed by a now-dead Maori man mediated by a machine [26, 27].

These mediated memories of bird calls can be further explored within studies of memory and music which posit that “the human’s recovery of the past is simultaneously embodied, enabled and embedded” [28]. Musical memories are often mediated through devices for listening, whether directly, such as by listening to (or playing) a musical instrument, or through the use of recording and playback equipment. It may be argued that musical notation itself is a form of recording and playback technology which can allow for concise repetitions of music[29-31]. Research has shown that recall is greatly improved if the same music is played during the recollection of an event as was played during the original experience [28]. Remembering music demands participation from the cognitive, emotive, and somatosensory areas of the brain. Repetition helps to keep it cycling through our working memory.

Could a recital comprised of calls of extinct or threatened birds, presented within a familiar framework of performance, evoke and recall birdcalls of the past; using the encounter between the two senior birdwatchers as the narrative framework?

In order to create such a performance, it will be necessary to provide the performers with the means of following a “score” so that they would be able to voice the calls at pre-determined times within the piece. This requires using or developing a notation for the birdcalls that would facilitate the performer in replicating the call.

There have been myriad attempts to capture the songs of birds – both long before and after the advent of recording technologies. These attempts have not always been mimetic; some are meant more to suggest the songs of birds, rather than to be actual representations of birdsong. An example of this would be Clément Janequin’s “Le Chant des oyseaulx” from 1529, which is an onomatopoetic chanson. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No.6 in F major from 1808, also known as the Pastoral Symphony, quotes three birds: the cuckoo, the quail, and the nightingale. Interestingly, it is thought that he “borrowed” liberally from Athanasius Kircher’s influential musicology treatise Musurgia Univeralis: Bird songs, published in 1650. There is also the well-known and oft-performed 13th-century English round Sumer Is Icumen In which also imitates the call of the cuckoo – a common motif, likely due to the simplicity of the call - and is one of the earliest examples of notated music [30]. There are countless instances throughout the centuries and across cultures, of composers attempting to incorporate birdsong in some fashion into their works.

In parallel with this musical preoccupation was the quest to develop some form of notation which could be used to record birdsong. Musical notation was one of the earliest conventions used, and Kircher’s Musurgia Univeralis is considered to be one of the first examples of this use. Musical notation is still used in depicting and recording birdsong today, as well as being used by some contemporary ornithologists. As a method to make field recordings it has many disadvantages, notably that not everyone can read and write music – I fall into that category, for example. It has also been argued that any form of transcription simplifies the original sounds[30, 32-34]. Aretas A. Saunders maintained that musical notation is unsuitable as birds utilize musical intervals not represented in our musical notation.[35] Using musical instruments to reproduce these sounds is also problematic, as the sounds produced by instruments can only approximate the actual birdsongs [4, 32, 34].

After the advent of recording equipment, composers began to incorporate the actual recordings of birds into their pieces. One of the first instances of a birdsong recording being used and deliberately scored into a work was Ottorino Respighi’s second orchestral work in his Roman Trilogy: The Pines of the Janiculum (I pini del Gianicolo: Lento). First performed in 1924, Respighi directed that a recording of a nightingale be made so that it could be played at the end of the movement, specifically on a Brunswick Panatrope record player. This was considered very avant-garde at the time, and quite sensational. This use of birdsong as objets trouvés is a tradition which carries on to today in contemporary music such as Pink Floyd’s Grantchester Meadows, from the experimental studio 1969 album Ummagumma. On this song, a taped loop of a skylark singing was heard in the background throughout.

The development of sound spectrographs, or sonographs, in the 1940’s demonstrated to ornithologists the great complexity of birdsong. “For the first time, the extraordinary virtuosity of the avian voice was revealed in all its glorious detail” wrote Peter Marler in his history of birdsong, Nature’s Music [36]. While sonograms graphically represent sound, they are not easily interpreted. Although there have been attempts to include sonograms in field guides, they have never come into popular usage [5, 32, 36]. That being said, as graphic representations of sound, modification of these visual notations may be possible, rendering them into effective directional tools.

As my intent would be to have human performers voice the call and response of my muses, I will not incorporate recordings into the performance, although I will make available any recordings to the performers as references. Additionally, for some species, there exists no extant recordings. In cases where they do exist, they may only represent a small portion of the bird’s call repertoire. Accordingly, a combination of methods of notation might serve to facilitate performers best.

Another method which I have chosen to explore is that of mnemonics. In a general sense, mnemonics describe any contrivance used as a memory aide. As regards our feathered friends, there is a long history of mnemonics used as onomatopoetic devices to recall bird sounds, and they are widely cross-cultural. These mnemonics endeavor to mimic the rhythms and sounds of the songs using words and phrases from human language, regardless of the lack of concurrence of equivalent sounds [25, 32, 36, 37]. John Bevis notes that this detachment can go further still: “rather than supply the rhythm of the song, the phrase for the chaffinch describes an event whose own rhythm suggests the song” in this case, “cricketer running to wicket, bowling” [32]. One of my personal favorites is the white-throated sparrow, with its “O sweet Canada, Canada, Canada”.

Novice birdwatchers are likely to try to identify birds by sight, while those who are more experienced will rely more on auditory cues [36, 38]. Many become quite astute at identifying birds by ear alone, and a good many can elicit a response from a targeted bird when they mimic their call.

This has led me to conclude that I want to have birdwatchers as my performers, as they will already be attuned to the nuances inherent in bird vocalizations. Additionally, through numerous field guides they would be familiar with the various methods of notation (A. Baker, personal communication, September 12, 2014). Expert birdwatchers are able to identify species even if the birdcalls are different from a standard. In other words, they are able to parse the various dialects of a given species’ vocabulary. This ability would be key in reproducing calls that they may not have direct experience with, as would possibly be the case with species that are extinct or threatened within a given geographic area (A. Baker, personal communication, September 17, 2014).

I propose using a combination of mnemonics and sonograms to create the score for the libretto. As I intend to present the work in Berlin, I will use a select list of German extinct or threatened birds [39] chosen in conjunction with ornithologists (T. Reinsch, personal communication, May 5, 2015; W. Hoffman, personal communication, July 15, 2015), their efficacy would be evaluated in consultation with birdwatchers - turning memory into narrative.

Turning memory into narrative is common practice in the human experience. Our memories become entwined with the recollections of others, so that each time we recall them they subtly change. This layering of narrative, or collective memory, can serve to reinforce our perceptions of both our past and potential futures [1, 2].

I am in the process of creating a libretto for a place-specific performance. The calls of extinct or threatened birds will be performed within a narrative crafted from my memories of an encounter between two elderly birdwatchers.

In using these bird calls, I hope to be able to transport my audience to an interior emotional setting whereby they may feel more sensitive to the absences in their environments.

As Ghassan Hage has said, “Song and music in particular, with their sub-symbolic meaningful qualities are often most appropriate in facilitating the voyage to this imaginary space of feelings”[3]. So too can sounds transport us [4-6].

The research with which I am engaged had its genesis in reminiscences at our family cottage in the Laurentian mountains of Québec about things no longer seen nor heard.

We all reminisced about what it used to sound like up there, about the complexity of the combined sounds of birds and wildlife. How the bass cacophony of bullfrogs in the evening could keep you from falling asleep, while the howling of the wolves nearby would make you shiver deliciously under the covers. The banshee laughing and wailing of loons would fade away to be replaced by the dignified hooting of owls.

It doesn’t sound like that anymore. To hear one bullfrog is cause to “shush” everyone, while the rare occasion that the wolves sing at night is remarked upon by all the neighbours, and is something you’d tell the cashier about at the store in town.

Visitors often remark now about the quality of the silence there, about how “beautiful and quiet” it is.

Is It?

We are firmly entrenched in a soon-to-be christened epoch, dubbed the “Anthropocene” by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and diatom biologist Eugene Stoermer. It is defined as a new geologic age in which the activities of humans have significantly impacted our global climate, environment and ecology to such an extent as to permanently mark the lithosphere. This age is commonly referred to as the “sixth extinction”, marked by rapid declines in biodiversity as more and more species become vulnerable to changes in their ecologies [7].

Reflecting upon what narrative I wanted to create, I realized how truly little we are aware of these losses in our surrounding environments. As the voices of species are extinguished, are we aware of these absences? Looking around our urban environments, we are confronted with false abundance – we may see a profusion of birds, but a paucity of species [8]. Have our environments become so cluttered with the sonic detritus of contemporary urban life that we are oblivious? Perhaps we confuse what we now hear with memories of what we once heard, or confabulate?

The writer Eva Hoffman declared, “Loss leaves a long trail in its wake. Sometimes, if the loss is large enough, the trail seeps and winds like invisible psychic ink through individual lives, decades, and generations” [9]. It has been has argued that “sharing memory is our default”, and that complex emotions such as grief, love and regret depend upon our personal memories and an awareness of the passing of time. Our imperfect recall is responsible for the endurance of the past within our present relationships [10, 11].

I thought about what the Laurentian forests and lakes would have sounded like in my grandparents’ time, and about the different species that they heard that I will never hear.

How could you describe the call of a bird you’d never heard? If you’d never heard it, could you truly miss it?

What remains between the song and the silence?

An encounter between two elderly birdwatchers spurred my interest in creating a work which not only speaks to my life-long fascination with birds, but examines this fascination in others. Through the use of birdcalls of extinct and threatened species, I wondered if it would be possible to foster a sense of awareness regarding what species we have already lost or are in the process of losing.

So what propelled me forward? Following a discussion with an ornithologist at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, I decided to see if I could get in touch with elderly birdwatchers who would have likely heard these species in the wild. Visiting a centenarian birdwatcher at a retirement home to look at his birdwatching diaries, and with the hope that I might be able to persuade him to do a few birdcalls, I was witness to a fascinating exchange. As he performed some bird calls for me, another elderly gentleman appeared in the doorway, and responded to the bird calls with calls of his own. The two engaged in a call and response of birdcalls for approximately thirty minutes. After the gentleman had left, I found out that due to dementia, he had been unable to hold conversations with others. Yet what I had witnessed was just that, using the voices of birds. It had been profoundly moving to watch and listen to the two men “converse”, and provoked a deeply visceral response in me.

What is it that makes birdsong so compelling? It would seem that it’s all in the genes. Charles Darwin believed that language acquisition is instinctual [12], and subsequent research by Noam Chomsky and his colleagues would seem to support this idea [13, 14]. Research has shown that the same set of genes that enables humans to speak also confers on birds the ability to sing [15-17]. It was further discovered that the way birds acquire specific birdsong seems to mirror the way humans acquire speech [17-20]. Dr. Doolittle’s exhortations to “talk to the animals” just might have some basis in fact.

Perhaps it also speaks to the notion of déjà vu, which refers to the phenomenon of feeling as though something is very familiar when in fact you are experiencing it for the first time. For Steve Goodman and Luciana Parisi,” déjà vu suggests time collapsed onto itself, perhaps some kind of mnemonic haunting or future feedback effect.” [21]. Paramnesia is usually described as a psychopathology in which events are remembered while being experienced for the first time. It is generally thought that this occurrence is far more commonplace than would be expected of a memory disorder. Henri Bergson described paramnesia as a “symptom that explains that there is a recollection of the present, contemporaneous with the present itself”[22, 23]. Thus the calls of songbirds may literally “speak” to our memories of nascent attempts to communicate conferring an uncanny familiarity with their songs.

It has been stated that “the importance of physical engagement with the world, through the senses, enables emotional expression to be made in artworks that can be perceived by both artist and audience”[24]. Furthermore, these memories of physical experiences spark creative cognition and stimulate the imagination. Mary Carruthers states:

“In Greek legend, memory, or Mnemosyne, is the mother of the Muses. That story places memory at the beginning, as the matrix of invention for all human arts, of all human making, including the making of ideas; it memorably encapsulates an assumption that memory and invention – what we now call creativity – if not exactly the same, are the closest thing to it. In order to create, in order to think at all, human beings require some mental tool or machine, and that machine lives in the intricate networks of their own memories. The requirement of memory for making new thoughts is at the heart of this traditional story [25].

Julianne Lutz Warren, a writer and conservation biologist, created a work entitled “Hopes Echo” for the Deutsches Museum in Munich (on exhibition until September 30, 2016). Her work concerns the “sound fossil” left by the huia bird of New Zealand, which became extinct in the beginning of the 20th century due primarily to habitat loss coupled with overhunting. There are no extant audio recordings of this bird – it became extinct before the technology was available to make field recordings. The Maori people regarded the huia as sacred, and those who were high status were accorded the honor of wearing its feathers or skins. To lure the birds when hunting, they learned to imitate its song. This was passed down through the generations, a practice that continued for decades after the bird became extinct. In 1954 a man named RAL Bateley made a recording of a Maori man, Henare Hkamma, whistling the huia’s call. Warren presents the audio recording of Hkamma’s bird calls with text drawing our attention to the fact that we have the calls of an extinct bird performed by a now-dead Maori man mediated by a machine [26, 27].

These mediated memories of bird calls can be further explored within studies of memory and music which posit that “the human’s recovery of the past is simultaneously embodied, enabled and embedded” [28]. Musical memories are often mediated through devices for listening, whether directly, such as by listening to (or playing) a musical instrument, or through the use of recording and playback equipment. It may be argued that musical notation itself is a form of recording and playback technology which can allow for concise repetitions of music[29-31]. Research has shown that recall is greatly improved if the same music is played during the recollection of an event as was played during the original experience [28]. Remembering music demands participation from the cognitive, emotive, and somatosensory areas of the brain. Repetition helps to keep it cycling through our working memory.

Could a recital comprised of calls of extinct or threatened birds, presented within a familiar framework of performance, evoke and recall birdcalls of the past; using the encounter between the two senior birdwatchers as the narrative framework?

In order to create such a performance, it will be necessary to provide the performers with the means of following a “score” so that they would be able to voice the calls at pre-determined times within the piece. This requires using or developing a notation for the birdcalls that would facilitate the performer in replicating the call.

There have been myriad attempts to capture the songs of birds – both long before and after the advent of recording technologies. These attempts have not always been mimetic; some are meant more to suggest the songs of birds, rather than to be actual representations of birdsong. An example of this would be Clément Janequin’s “Le Chant des oyseaulx” from 1529, which is an onomatopoetic chanson. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No.6 in F major from 1808, also known as the Pastoral Symphony, quotes three birds: the cuckoo, the quail, and the nightingale. Interestingly, it is thought that he “borrowed” liberally from Athanasius Kircher’s influential musicology treatise Musurgia Univeralis: Bird songs, published in 1650. There is also the well-known and oft-performed 13th-century English round Sumer Is Icumen In which also imitates the call of the cuckoo – a common motif, likely due to the simplicity of the call - and is one of the earliest examples of notated music [30]. There are countless instances throughout the centuries and across cultures, of composers attempting to incorporate birdsong in some fashion into their works.

In parallel with this musical preoccupation was the quest to develop some form of notation which could be used to record birdsong. Musical notation was one of the earliest conventions used, and Kircher’s Musurgia Univeralis is considered to be one of the first examples of this use. Musical notation is still used in depicting and recording birdsong today, as well as being used by some contemporary ornithologists. As a method to make field recordings it has many disadvantages, notably that not everyone can read and write music – I fall into that category, for example. It has also been argued that any form of transcription simplifies the original sounds[30, 32-34]. Aretas A. Saunders maintained that musical notation is unsuitable as birds utilize musical intervals not represented in our musical notation.[35] Using musical instruments to reproduce these sounds is also problematic, as the sounds produced by instruments can only approximate the actual birdsongs [4, 32, 34].

After the advent of recording equipment, composers began to incorporate the actual recordings of birds into their pieces. One of the first instances of a birdsong recording being used and deliberately scored into a work was Ottorino Respighi’s second orchestral work in his Roman Trilogy: The Pines of the Janiculum (I pini del Gianicolo: Lento). First performed in 1924, Respighi directed that a recording of a nightingale be made so that it could be played at the end of the movement, specifically on a Brunswick Panatrope record player. This was considered very avant-garde at the time, and quite sensational. This use of birdsong as objets trouvés is a tradition which carries on to today in contemporary music such as Pink Floyd’s Grantchester Meadows, from the experimental studio 1969 album Ummagumma. On this song, a taped loop of a skylark singing was heard in the background throughout.

The development of sound spectrographs, or sonographs, in the 1940’s demonstrated to ornithologists the great complexity of birdsong. “For the first time, the extraordinary virtuosity of the avian voice was revealed in all its glorious detail” wrote Peter Marler in his history of birdsong, Nature’s Music [36]. While sonograms graphically represent sound, they are not easily interpreted. Although there have been attempts to include sonograms in field guides, they have never come into popular usage [5, 32, 36]. That being said, as graphic representations of sound, modification of these visual notations may be possible, rendering them into effective directional tools.

As my intent would be to have human performers voice the call and response of my muses, I will not incorporate recordings into the performance, although I will make available any recordings to the performers as references. Additionally, for some species, there exists no extant recordings. In cases where they do exist, they may only represent a small portion of the bird’s call repertoire. Accordingly, a combination of methods of notation might serve to facilitate performers best.

Another method which I have chosen to explore is that of mnemonics. In a general sense, mnemonics describe any contrivance used as a memory aide. As regards our feathered friends, there is a long history of mnemonics used as onomatopoetic devices to recall bird sounds, and they are widely cross-cultural. These mnemonics endeavor to mimic the rhythms and sounds of the songs using words and phrases from human language, regardless of the lack of concurrence of equivalent sounds [25, 32, 36, 37]. John Bevis notes that this detachment can go further still: “rather than supply the rhythm of the song, the phrase for the chaffinch describes an event whose own rhythm suggests the song” in this case, “cricketer running to wicket, bowling” [32]. One of my personal favorites is the white-throated sparrow, with its “O sweet Canada, Canada, Canada”.

Novice birdwatchers are likely to try to identify birds by sight, while those who are more experienced will rely more on auditory cues [36, 38]. Many become quite astute at identifying birds by ear alone, and a good many can elicit a response from a targeted bird when they mimic their call.

This has led me to conclude that I want to have birdwatchers as my performers, as they will already be attuned to the nuances inherent in bird vocalizations. Additionally, through numerous field guides they would be familiar with the various methods of notation (A. Baker, personal communication, September 12, 2014). Expert birdwatchers are able to identify species even if the birdcalls are different from a standard. In other words, they are able to parse the various dialects of a given species’ vocabulary. This ability would be key in reproducing calls that they may not have direct experience with, as would possibly be the case with species that are extinct or threatened within a given geographic area (A. Baker, personal communication, September 17, 2014).

I propose using a combination of mnemonics and sonograms to create the score for the libretto. As I intend to present the work in Berlin, I will use a select list of German extinct or threatened birds [39] chosen in conjunction with ornithologists (T. Reinsch, personal communication, May 5, 2015; W. Hoffman, personal communication, July 15, 2015), their efficacy would be evaluated in consultation with birdwatchers - turning memory into narrative.

Endnotes

1. Miller, G., A surprising connection between memory imagination.(NEUROBIOLOGY). Science, 2007. 315(5810): p. 312.

2. Freeman, M., Telling Stories: Memory and Narrative, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 263-277.

3. Hage, G., Migration, Food, Memory, and Home-Building, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. 416-427.

4. Rohrmeier, M., et al., Principles of structure building in music, language and animal song. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 2015. 370(1664): p. 107-121.

5. Soha, J.A. and S. Peters, Vocal Learning in Songbirds and Humans: A Retrospective in Honor of Peter Marler. 2015. p. 933-945.

6. Stimpson, C.R., The Somagrams of Gertrude Stein. Poetics Today, 1985. 6(1/2): p. 67-80.

7. Kolbert, E., The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. First ed. 2014, New York: Henry Holt and company. 336.

8. Strohbach, M., D. Haase, and N. Kabisch, Birds and the City: Urban Biodiversity, Land Use, and Socioeconomics. Ecology And Society, 2009. 14(2).

9. Hoffman, E., The Long Afterlife of Loss, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: Ashland, Ohio. p. pp 406-415.

10. Sutton, J., C.B. Harris, and A.J. Barnier, Memory and Cognition, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 209-226.

11. Campbell, S., The second voice. Memory Studies, 2008. 1(1): p. 41-48.

12. Richards, R.J., Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary theories of mind and behavior. Science and its conceptual foundations. 1987, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. xvii, 700 p.

13. Hauser, M.D., N. Chomsky, and W. Fitch, The faculty of language: What is it, who has it, and how did it evolve?, in Science. 2002. p. 1569- 1579.

14. Pinker, S., The language instinct : the new science of language and mind. 1994: Penguin.

15. Scharff, C. and I. Adam, Neurogenetics of birdsong. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2013. 23(1): p. 29-36.

16. Olias, P., et al., Reference Genes for Quantitative Gene Expression Studies in Multiple Avian Species. Plos One, 2014. 9(6): p. 12.

17. Scharff, C. and S.A. White, Genetic Components of Vocal Learning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2004. 1016(1): p. 325-347.

18. Bolhuis, J.J., K. Okanoya, and C. Scharff, Twitter evolution: converging mechanisms in birdsong and human speech. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2010. 11(11): p. 747-759.

19. Scharff, C. and J. Petri, Evo-devo, deep homology and FoxP2: implications for the evolution of speech and language. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 2011. 366(1574): p. 2124-2140.

20. White, S.A., et al., Singing mice, songbirds, and more: Models for FOXP2 function and dysfunction in human speech and language. Journal of Neuroscience, 2006. 26(41): p. 10376-10379.

21. Goodman, S. and L. Parisi, Machines of Memory, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 343-359.

22. Bergson, H., Matière et mémoire; essai sur la relation du corps à l'esprit. 36. éd. ed. Bibliothèque de philosophie contemporaine. 1941, Paris,: Presses universitaires de France. 2 p. l., 280, 2 p.

23. Bergson, H., Matter and memory. 1988, New York: Zone Books. 284 p.

24. Treadaway, C., Translating experience. Interacting with Computers, 2009. 21(1): p. 88-94.

25. Carruthers, M., How to Make a Composition, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S.e. Radstone and B.e. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 15-29.

26. Tekula, S. The Poetry Lab: “Hopes Echo” by Author Julianne Warren. 2015 2015-11-03; Available from: http://www.merwinconservancy.org/2015/11/the-poetry-lab-hopes-echo-by-author-julianne-warren-center-for-humans-and- nature/ .

27. Macfarlane, R. Generation Anthropocene: How Humans have altered the planet. 2016 [cited 2016 April 1, 2016]; Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/01/generation-anthropocene-altered-planet-for-ever.

28. Dijck, J.v., Mediated memories in the digital age. Cultural memory in the present. 2007, Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. xviii, 232 p.

29. Meyer, L.B., Emotion and meaning in music. 1956, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. xi, 307 p.

30. Gould, E., Behind Bars: The Definitive Guide to Music Notation. 2011, England: Faber Music Ltd. 676.

31. Edgerton, M.E., The 21st Century Voice. The New Instrumentation Series (Book 9). 2004: Scarecrow Press.

32. Bevis, J., Aaaaw to zzzzzd : the words of birds : North America, Britain, and northern Europe. 2010, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 143 p.

33. Phillips, T. Graphic music scores - in pictures. 2013 2013-10-04; Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2013/oct/04/graphic-music-scores-in-pictures.

34. Mathews, F.S., Field book of wild birds and their music; a description of the character and music of birds, intended to assist in the identification of species common in the eastern U.S. 1904, New York etc.: G.P. Putnam's sons. xxxv, 262 p.

35. Saunders, A.A., A Guide to Bird Songs. 1936, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

36. Marler, P. and H.W. Slabbekoorn, Nature's music : the science of birdsong. 2004, Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier Academic. xviii, 513 p., 12 p. of plates.

37. Dudai, Y. and M. Carruthers, The Janus face of Mnemosyne. Nature, 2005. 434(7033): p. 567.

38. Kroodsma, D. Understanding birds through their songs. May 10, 2009 [cited 2016 April 6]; Available from: https://www.newscientist.com/gallery/mg20227071600-birdsong-by-the-seasons/.

39. Carruthers, D. Between the Song and the Silence: Select German Extinct or Threatened Bird Species. 2016 May 1, 2016; Available from: http://www.deborahcarruthers.com/8203select-german-extinct-or-threatened-bird-species.html.

1. Miller, G., A surprising connection between memory imagination.(NEUROBIOLOGY). Science, 2007. 315(5810): p. 312.

2. Freeman, M., Telling Stories: Memory and Narrative, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 263-277.

3. Hage, G., Migration, Food, Memory, and Home-Building, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. 416-427.

4. Rohrmeier, M., et al., Principles of structure building in music, language and animal song. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 2015. 370(1664): p. 107-121.

5. Soha, J.A. and S. Peters, Vocal Learning in Songbirds and Humans: A Retrospective in Honor of Peter Marler. 2015. p. 933-945.

6. Stimpson, C.R., The Somagrams of Gertrude Stein. Poetics Today, 1985. 6(1/2): p. 67-80.

7. Kolbert, E., The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. First ed. 2014, New York: Henry Holt and company. 336.

8. Strohbach, M., D. Haase, and N. Kabisch, Birds and the City: Urban Biodiversity, Land Use, and Socioeconomics. Ecology And Society, 2009. 14(2).

9. Hoffman, E., The Long Afterlife of Loss, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: Ashland, Ohio. p. pp 406-415.

10. Sutton, J., C.B. Harris, and A.J. Barnier, Memory and Cognition, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 209-226.

11. Campbell, S., The second voice. Memory Studies, 2008. 1(1): p. 41-48.

12. Richards, R.J., Darwin and the emergence of evolutionary theories of mind and behavior. Science and its conceptual foundations. 1987, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. xvii, 700 p.

13. Hauser, M.D., N. Chomsky, and W. Fitch, The faculty of language: What is it, who has it, and how did it evolve?, in Science. 2002. p. 1569- 1579.

14. Pinker, S., The language instinct : the new science of language and mind. 1994: Penguin.

15. Scharff, C. and I. Adam, Neurogenetics of birdsong. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2013. 23(1): p. 29-36.

16. Olias, P., et al., Reference Genes for Quantitative Gene Expression Studies in Multiple Avian Species. Plos One, 2014. 9(6): p. 12.

17. Scharff, C. and S.A. White, Genetic Components of Vocal Learning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2004. 1016(1): p. 325-347.

18. Bolhuis, J.J., K. Okanoya, and C. Scharff, Twitter evolution: converging mechanisms in birdsong and human speech. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2010. 11(11): p. 747-759.

19. Scharff, C. and J. Petri, Evo-devo, deep homology and FoxP2: implications for the evolution of speech and language. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 2011. 366(1574): p. 2124-2140.

20. White, S.A., et al., Singing mice, songbirds, and more: Models for FOXP2 function and dysfunction in human speech and language. Journal of Neuroscience, 2006. 26(41): p. 10376-10379.

21. Goodman, S. and L. Parisi, Machines of Memory, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S. Radstone and B. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 343-359.

22. Bergson, H., Matière et mémoire; essai sur la relation du corps à l'esprit. 36. éd. ed. Bibliothèque de philosophie contemporaine. 1941, Paris,: Presses universitaires de France. 2 p. l., 280, 2 p.

23. Bergson, H., Matter and memory. 1988, New York: Zone Books. 284 p.

24. Treadaway, C., Translating experience. Interacting with Computers, 2009. 21(1): p. 88-94.

25. Carruthers, M., How to Make a Composition, in Memory : histories, theories, debates, S.e. Radstone and B.e. Schwarz, Editors. 2010, Fordham University Press: New York. p. pp 15-29.

26. Tekula, S. The Poetry Lab: “Hopes Echo” by Author Julianne Warren. 2015 2015-11-03; Available from: http://www.merwinconservancy.org/2015/11/the-poetry-lab-hopes-echo-by-author-julianne-warren-center-for-humans-and- nature/ .

27. Macfarlane, R. Generation Anthropocene: How Humans have altered the planet. 2016 [cited 2016 April 1, 2016]; Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/01/generation-anthropocene-altered-planet-for-ever.

28. Dijck, J.v., Mediated memories in the digital age. Cultural memory in the present. 2007, Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. xviii, 232 p.

29. Meyer, L.B., Emotion and meaning in music. 1956, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. xi, 307 p.

30. Gould, E., Behind Bars: The Definitive Guide to Music Notation. 2011, England: Faber Music Ltd. 676.

31. Edgerton, M.E., The 21st Century Voice. The New Instrumentation Series (Book 9). 2004: Scarecrow Press.

32. Bevis, J., Aaaaw to zzzzzd : the words of birds : North America, Britain, and northern Europe. 2010, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 143 p.

33. Phillips, T. Graphic music scores - in pictures. 2013 2013-10-04; Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2013/oct/04/graphic-music-scores-in-pictures.

34. Mathews, F.S., Field book of wild birds and their music; a description of the character and music of birds, intended to assist in the identification of species common in the eastern U.S. 1904, New York etc.: G.P. Putnam's sons. xxxv, 262 p.

35. Saunders, A.A., A Guide to Bird Songs. 1936, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

36. Marler, P. and H.W. Slabbekoorn, Nature's music : the science of birdsong. 2004, Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier Academic. xviii, 513 p., 12 p. of plates.

37. Dudai, Y. and M. Carruthers, The Janus face of Mnemosyne. Nature, 2005. 434(7033): p. 567.

38. Kroodsma, D. Understanding birds through their songs. May 10, 2009 [cited 2016 April 6]; Available from: https://www.newscientist.com/gallery/mg20227071600-birdsong-by-the-seasons/.

39. Carruthers, D. Between the Song and the Silence: Select German Extinct or Threatened Bird Species. 2016 May 1, 2016; Available from: http://www.deborahcarruthers.com/8203select-german-extinct-or-threatened-bird-species.html.